BluesCat is a resident of Phoenix, Arizona, who originally returned to bicycling in 2002 in order to help his son get the Boy Scout Cycling merit badge. His bikes sat idle until the summer of 2008 when gas prices spiked at over $4.00 per gallon. Since then, he has become active cycling, day-touring, commuting by bike, blogging (azbluescat.blogspot.com) and giving grief to the forum editors in the on-line cycling community.

BluesCat is a resident of Phoenix, Arizona, who originally returned to bicycling in 2002 in order to help his son get the Boy Scout Cycling merit badge. His bikes sat idle until the summer of 2008 when gas prices spiked at over $4.00 per gallon. Since then, he has become active cycling, day-touring, commuting by bike, blogging (azbluescat.blogspot.com) and giving grief to the forum editors in the on-line cycling community.

Finally! In a post about his sweaty experiences using Capital Bikeshare in Washington, DC, Ted Johnson admits to seeing the benefits of an e-bike!

You see, I’ve lived in the same mountaintop community where Ted does. The worst sweating that I did in Flagstaff was when I was splitting firewood one December… in a t-shirt… in a snow storm.

People up there don’t know sweat. Residents in my present hometown of Phoenix — with summer highs of 115 degrees Fahrenheit breaking silly “residential thermometers” — certainly know something about sweat.

However, the people who really know their sweat are the folks who live somewhere along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, or anybody anywhere on the Florida peninsula. If you live in one of those places, you can actually watch the mold growing on your stuff; like something out of a B-movie: Attack of the Killer Fungus. The high humidity for you Kings of Perspiration keeps the Heat Index (H.I.) up at stratospheric heights.

For anyone unfamiliar with the term “heat index,” the dictionary definition is “a number representing the effect of temperature and humidity on humans by combining the two variables into an “apparent’ temperature.” For “an apparent temperature” they sometimes substitute “a measure of how hot it actually feels.”

But I don’t like that description. I would much prefer “a measure of how sick you’re going to get.”

The simple fact is that as the relative humidity goes up, evaporation slows and your sweat removes heat from your body at a lower rate. So when the humidity is really high, the heat index formula will show that the “apparent temperature” is actually higher than what the thermometer reads.

For example, when the temperature in New Orleans, Louisiana, is 84 °F, and the humidity is 76%, the heat index formula calculates that the apparent temperature is something like 93 °F; or in the “Extreme Caution” range of the Heat Index.

In Phoenix, Arizona, in the spring, when temperature is at is 93 °F but the humidity is in the single digits at 9% (known as our famous “dry heat”), the heat index is only around 89 °F; in the mere “Caution” range of the Heat Index.

Here’s a table showing the effects of the various heat index ranges:

| Celsius | Fahrenheit | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 27"“32 °C | 80"“90 °F | Caution "” fatigue is possible with prolonged exposure and activity. Continuing activity could result in heat cramps |

| 32"“41 °C | 90"“105 °F | Extreme Caution "” heat cramps and heat exhaustion are possible. Continuing activity could result in heat stroke |

| 41"“54 °C | 105"“130 °F | Danger "” heat cramps and heat exhaustion are likely; heat stroke is probable with continued activity |

| over 54 °C | over 130 °F | Extreme Danger "” heat stroke is imminent |

Right after this table on the Wikipedia page, they included this important additional information: “Exposure to full sunshine can increase heat index values by up to 8 °C (14 °F).” This is all the more reason to seek out shaded bike routes and wear the proper clothing on bright, sunny days.

This Wiki-table is pretty much in line with my own, personal heat index. As a longtime desert rat, who has experienced heat exhaustion twice and knows the early warning signs, I can push the Extreme Caution range up to round 110 °F. Anything above that and I’m off the bike, I don’t need to complicate life for myself or the EMT’s.

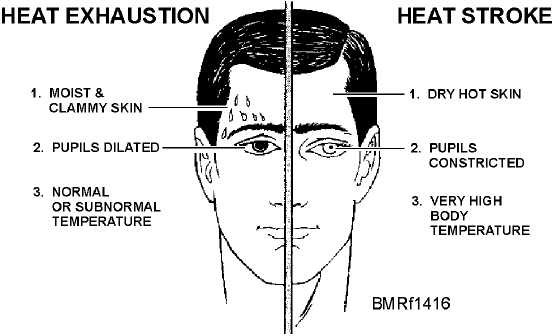

The symptoms of heat exhaustion can vary between individuals. Some people suddenly begin sweating much more than they were a few minutes before, their breathing speeds up and their pulse may quicken. Unfortunately, these are usually the same signs of exertion from any sort of exercise, and some will chide themselves for being wimps and continue on with their ride. Big mistake; by the time they get to the really heavy symptoms of dizziness, nausea and cramps, they may be well on their way to heat stoke and real danger.

I’m pretty lucky, my symptoms of heat illness always begin with the dizziness. When I had my first bout of heat exhaustion, I was backpacking and I got dizzy and immediately took a break. I was okay after about an hour of sitting, having something to eat and drinking some water.

I wasn’t so smart the second time. I was hiking, got dizzy and thought, “Heck, I’m going to quit and set up camp in a mile or so anyway, so I’ll just tough it out.” Again, big mistake: Minutes later I was puking, stumbling from the cramps and was lucky to make it to the shade of a little tree where I spent the rest of the day and night.

Here’s the key: Anytime you’re outdoors and you start to feel “not right,” STOP, find some shade if you are out in the sun, get a drink of water, and see how you feel in a few minutes. If you feel okay, then continue, if not then make arrangements to quit for the day. You won’t be labeled a “hero” or “real macho” if you try to “battle through the discomfort,” you’ll be called a “dead idiot.” Discomfort is the first indicator your body uses to alert you of things being “not right.” Pay attention to it and you’ll stay out of trouble.

If you prepare well for your bike outing, your chances of ever feeling “not right” are greatly reduced. Check the weather service to see if there are any extreme heat warnings for the area where you’ll be riding and the time frame of your trip; if there are schedule your riding for another day. If you have a smartphone, there are a number of apps available (like Weatherbug) which will keep you up-to-date about such warnings.

Check with local bike shops and hiking clubs about the smartest clothing to wear when you’re out exercising in the area. The right clothing for a desert area is not the right stuff for a rain forest.

My daily intake of salty, spicy Mexican food and copious amounts of beer means that I always have enough electrolytes in my system, but if your diet doesn’t include Belgian wheat ale as one of your most important food groups, you might want to be sure to have a bottle of some sort of sport drink with you when you ride.

And always, always, always take along plenty of water, no matter where you go outdoors. My bikes are festooned with bottle cages, two on each of my mountain bikes and three on my recumbent. Three 24-ounce bottles provide plenty of water for my eight mile trip home in the afternoon. If your ride takes you farther than that, you should probably look into a hydration system like a Dakine or a Camelbak.

Both these manufacturers make stylish packs for their hydration system reservoirs, but if you use a backpack and want something designed with bicyclists in mind, go with one of the Vaude bicycling-specific backpacks like the Hyper Air 14-3 or the Trail Light 12. Not only do these bags have an integrated hydration system, they are also designed to stay in place for mountain bikers plummeting down insanely steep hills. They’ll be perfect for your bike commute.

By all means drink all that water, too! My commute crosses several major streets where I have to wait for traffic lights; I use those pauses to take a couple healthy hits of water and pour some over the vents in my helmet. Drinking plenty of water isn’t some magic shield against heat illness, you need to make sure you pay attention to the heat index and your own body, but without the intake of a lot of water, you won’t sweat enough to regulate your internal temperature, and you won’t know sweat, Jack!